Remembering a local legend: Lorna de Smidt leaves behind legacy in anti-apartheid fight

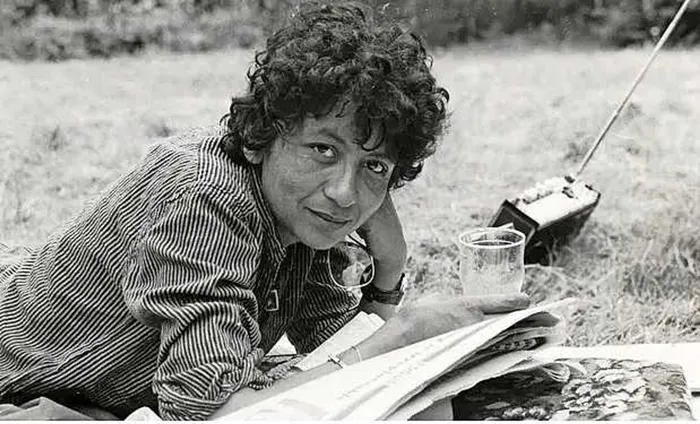

REST IN PEACE, FIGHTER: Activist Lorna de Smidt

Today we honour the extraordinary life of a local anti-apartheid, equality and women’s rights activist, teacher and journalist, Lorna de Smidt, who passed away recently.

The following is an obituary by her husband Graham de Smidt.

My wife, Lorna de Smidt, who has died aged 78 from peripheral vascular disease, was an anti-apartheid and anti-racism activist who cut her political teeth in the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa in the late 1960s and came to the UK as a refugee.

In 1976, she was teaching in Cape Town when the government ruled Afrikaans would become the medium in black schools, leading to the Soweto Uprising.

Lorna’s students poured on to the streets in solidarity. Soon after, she was imprisoned for two and a half months in the notorious Roeland Street jail under section 10 of the Internal Security Act. No charges, no trial.

One of six children, Lorna was born in Kensington, Cape Town, to Ronald Matthee, a welder, and Helen (nee Davids).

After Trafalgar High School, she trained at Zonnebloem Teacher Training College, Wynberg, finishing in the late 60s, and taught English at schools in Cape Town.

At the time of the Soweto uprising, she was working at Salt River High School.

We met in 1977 and were illegally married the same year by the Rev Theo Kotze.

We knew the apartheid police would quickly act to attack this “illegal” relationship. The strategy was familiar – if arrested, the black partner of a “mixed race” couple would receive a six-month prison sentence for “immorality”, the white a suspended sentence.

We decided to quit the country. It meant leaving behind her four-year-old twins with their father, Daoud Meeran, her former partner.

After a defiant wedding party in Cape Town, the journey into exile began.

Lorna was without a passport; mine was confiscated as I attempted to catch a flight. Lorna’s 14-year-old son, Emile, flew to London on his own.

After a period in hiding, we were spirited across the border into Botswana. The following year we travelled to London as refugees, using documents provided by the UN.

Once in the UK, Lorna, with our new baby daughter on her hip, threw herself into struggles for justice, equality and women’s rights, and against racism.

She hosted striking Nottingham black miners, travelled with Sunderland miners to raise funds in the Netherlands and cooked pots of food for actors in the Greenwich Young People’s theatre.

She worked as a freelance journalist, investigating Craig Williamson, the notorious secret police agent, for the Dutch newspaper Vrij Nederland.

From 1983 to 1991 she worked for the Lewisham Race Equality Unit and helped develop two documentaries shown by the BBC, Suffer the Children (1988), on the torture and imprisonment of children by the apartheid state, and How I’d Love to Feel Free (1989), about the influence of roots music in the cultural South African story.

After Nelson Mandela’s release in 1990, Lorna returned to South Africa to participate in the first free election as an observer and voter – and was reunited with her twins, by now 18 years old.

In the late 90s, Cheryl Carolus, her fellow prison detainee of 1976, was appointed South Africa’s High Commissioner in London, and invited Lorna to transform South Africa House in Trafalgar Square from an old colonial show piece with its racist murals into a modern African legation.

She consulted widely and came up with a groundbreaking plan to re-contextualise and interpret the murals using the work of contemporary South African artists.

As Lorna’s health deteriorated, her iPad became her “keyboard weapon” – her anger fuelling her most recent targets: UK and SA corruption, defending Palestinian human rights, and freedom for Julian Assange.

Lorna is survived by me, her son Emile from an earlier relationship, her twins, Jean and Zinaid, and our daughter Leila.